prohibition and churches (wine and the kingdom p3)

At the back of Ty's grandfather's Decatur church is a large framed document with flourished script. It hangs on the wall as the charter or constitution that originally formed the small Baptist church. It declares the Bible-centered purpose of the new congregation, and lays down some basic beliefs. Among those is a condemnation of alcohol, and the promise that members will not drink it. But it goes further, pledging that members will not attend dinner parties where wine may be served, or purchase groceries from stores that carry alcohol. For years, this regulation sent members across town to the last family-owned store that abstained. These days, there's no longer a choice.

At the back of Ty's grandfather's Decatur church is a large framed document with flourished script. It hangs on the wall as the charter or constitution that originally formed the small Baptist church. It declares the Bible-centered purpose of the new congregation, and lays down some basic beliefs. Among those is a condemnation of alcohol, and the promise that members will not drink it. But it goes further, pledging that members will not attend dinner parties where wine may be served, or purchase groceries from stores that carry alcohol. For years, this regulation sent members across town to the last family-owned store that abstained. These days, there's no longer a choice.

Why do we live an a culture in the American 20th and 21st century where groups of Christians treat wine with suspicion or hostility, declaring it unfit for association with the Kingdom?

I sat down and had a conversation with Dr. Adrian Lamkin on this very subject. Professor Lamkin is a scholar of Church History, with a special expertise on the late American church. Personally raised as a conservative Kentucky Baptist, Dr. Lamkin understands this phenomenon. I asked him if he could trace some historical roots.

(this isn't verbatim, it's my shortened recollection of our hour-long conversation. Any errors are quite definitely mine.)

Me: Do you see another time in church history where the church saw drinking alcohol as wrong or sinful?

Dr. Lamkin: Well, no. No, not really. It seems that most of the church fathers would have not have seen this as a topic to write about… they assumed that church members would consume alcohol going about their regular lives. From Augustine to Luther to CS Lewis... well, much theology was done in the pub, wasn't it?

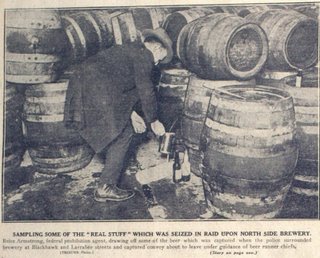

Me: I've recently read more about the history of the Prohibition movement in the early 1900's, and the passage of the 18th Amendment in 1920 banning the sale of alcohol in the United States [subsequently repealed in 1929]. I noticed at the time that church groups were some of prohibition's most prominent supporters.

Dr. Lamkin: Yes, church groups and women's suffrage groups. The most prominent three denominations in the late 1800's and early 20th century were Methodist, Lutheran, and Presbyterian. They played a primary role. Baptists and Episcopals wouldn't have as much influence until later on.

Me: I read the text of several 1920 sermons celebrating the new prohibition with glorious language - promising the beginning of a new era of the Kingdom of God - an end to poverty and sin in our nation. What were the factors that lead the American churches to that viewpoint?

Dr. Lamkin: Okay. I can think of three things. And they aren't as obvious as you'd think.

Slavery. In the wake of the civil war, there was a path of thought in the church that felt guilty about their verbal absence in condemning slavery. New pastors and leaders felt a burden to speak morality into the culture (as opposed to isolation). They looked for a place of influence. It had a unifying effect on the protestant denominations - a common reason to speak with one voice on a new issue.

Whiskey. We really did have a drinking problem as a nation. The late 1800's brought stories of the abandoned families of drunken farmers. Europe was referring to us as the "whiskey nation." Kentucky corn growers could make more money shipping their corn in a fermenting tub down the Mississippi River then trying to lug it over the mountains to the East Coast market. This "whiskey mash" was a major export.

Me: Really? But certainly not a drinking problem more than today.

Dr. Lamkin: Oh yes, really. It was quite bad. The "temperance" movement, advocating a more controlled use of alcohol, was earlier than the prohibition movement. It was a reasonable response to a real problem.

Me: Okay, what else?

Dr. Lamkin: Immigration. It was changing around the turn of the century, especially from Europe. Less Western Europeans from France, Italy, etc, and more Eastern Europe, like from Poland. What's the difference between these groups?

Me: I'm not sure.

Dr. Lamkin: The former were mostly Protestant, while the newer immigrants were Catholic. They had no social theology curbing alcohol, and forming poor communities in cities, became viewed as the out-of-work, "over-the tracks" drinking poor. This is the link to poverty - some felt eliminating alcohol from the nation would cure these neighborhoods and provide the moral leadership needed to get the working. But probably their drinking had less to do with their economic status than other factors, such as the job market.

Me: Wow. So the guilt over slavery, the change in immigration, and our whiskey exports helped formed the theology we hear today from many fundamentalist churches? Huh. I wonder what some of my conservative Baptist brothers would think of that explanation if I said it?

So then help me make this connection. When looking at Jesus in the gospels, especially regarding his first miracle, "The Water to Wine" – I've heard some explanations that the ancient world watered their wine, and it wasn’t really alcoholic in the way we think today. Is this true?

Dr. Lamkin: No, no, not really. True that they watered down the wine. But the wine was very concentrated to begin with ("strong wine" in some translations; "mixed wine" includes water). It probably mixed it down to the strength of beer today 5-6% alcohol. Still quite enough for one to feel the effect.

Me: Which makes sense, because if the wine wasn't really alcoholic, why would the Bible contain the warnings against drunkenness?

Dr. Lamkin: Exactly. But notice that this historical revision comes from when? Commentators from the early 1900s. Makes sense. It was hard preach 100% abstinence if Jesus drank wine! This essentially needed to be explained away.

--

Interesting, huh? What do you think?